Cardboard… Such an underrated material. People use it mostly for packaging, but there’s so much more to it. (I’m joking, of course. Do you remember the Google Cardboard project?)

Cardboard… Such an underrated material. People use it mostly for packaging, but there’s so much more to it. (I’m joking, of course. Do you remember the Google Cardboard project?)

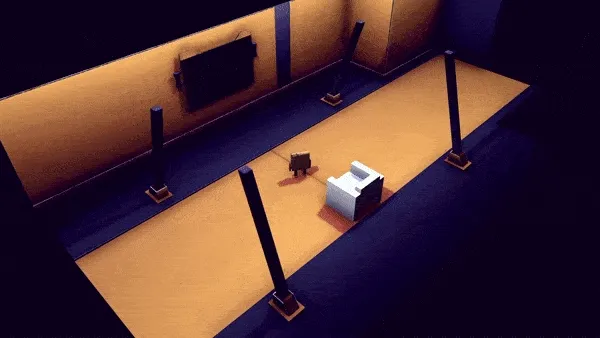

The idea of using cardboard as the main texture in our game first came up during a brainstorming session for our next hypercasual mobile game. We hadn’t even made a prototype out of it, but I remember it being something like 3D origami made of cardboard. Not gonna lie, that was a few years ago, I don’t remember the details.

But that was just the seed of the idea; we had no idea where it would lead. The real breakthrough came during one of Krystof’s streams (my ex-colleague from Mad Cookies). At that time, we were primarily focused on outsourcing, but we also dedicated some of our free time to prototyping new concepts that could evolve into a full-blown project. Anyway, during a game jam (where most of our best ideas emerged) Krystof brainstormed the visuals for the game and mentioned the cardboard-y hypercasual game concept to his chat.

I’d like to put it this way: THE CHAT WENT CRAZY (myself included, as I watched many of his streams at that time).

The following Monday we had a company meeting about whatever was needed at that time, but most importantly, the (at least we thought so) potential gold mine we hit with the cardboard visuals.

A few brainstorming sessions later, Cardbob was born.

Why Godot?

Back then, the latest version of the Godot Engine was, I think, 3.4, and the number of popular games made with it was dangerously close to zero. So, naturally, when I mentioned we were using Godot to make Cardbob, I usually got one of two responses:

- Huh, cool. What’s Godot?

- Why not Unity?

Thanks to the Unity fiasco, many of you now know the answer to the first question, but the second one is a bit more specific. Like I mentioned earlier, we were deep into outsourcing at the time (either as freelancers or a whole studio), and we still had active projects that we couldn’t just abandon — our wallets wouldn’t allow it. So, since Krystof wasn’t needed full-time on other projects, he got to spearhead the Cardbob prototype while the rest of us wrapped up our projects.

Alright, that didn’t really answer the question. We were quite uncertain about the deadlines for our outsourcing projects, given their unpredictable nature (that’s a long story!). Because of this fact, we knew that following the traditional route of making a super quick prototype, scrapping it, and starting over properly just wouldn’t work in our favor. Also, Krystof isn’t a programmer by training; he’s a self-taught coder who started out as a solo developer and mainly a 3D artist before joining Mad Cookies. He wanted to make games and wasn’t a fan of Unity, so he picked up Godot.

And just like that, Godot it was. Well, it was a bit more than just that. As a developer myself, I understand the concepts and can switch frameworks with ease — I figured I could just pick up the engine-specific details on the fly while untangling our prototype’s spaghetti code.

January 1, 2022, marked the very first day of Cardbob’s development. A month later, I officially joined the team and started to refactor things. Surprisingly, it wasn’t that bad—both working with the engine and rewriting things proved to be fairly quick tasks.

Cardboard

Also, cardboard has proven itself to be not just an interesting material, but it has also significantly sped up development, by a lot. If you don’t believe me, consider this:

the game primarily uses just these two main textures:

Also, not only was development accelerated, but the GPU hardly breaks a sweat during rendering. This efficiency is due to almost everything being batched, thanks to the limited use of materials and textures.

Also, not only was development accelerated, but the GPU hardly breaks a sweat during rendering. This efficiency is due to almost everything being batched, thanks to the limited use of materials and textures.

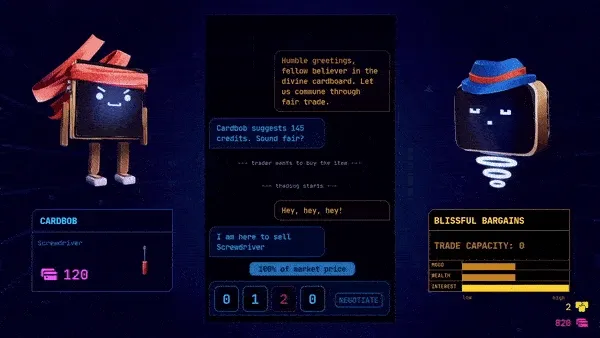

Now, I want to dive into the features themselves — but I’ll start with something you might not expect in an action roguelite: item trading with negotiation mechanics.

Price negotiation

Yes, we considered using GPT for role-playing, but it wasn’t quite effective at that time. We also aimed for something a bit predictable (yet not entirely). This part, I believe, was one of the most rewritten aspects of the game.

Traders

First off, the traders. The game features four trader personas:

- Angry

- Happy

- Pessimistic

- Religious

These personas not only influence the visual aspects of the traders (like their names and visuals) but also their chat responses. Each trader has a unique set of reactions to your offer or counteroffer, providing clues about their reasoning behind their counteroffers.

Regardless of their persona, each trader has three stats influencing their reactions, their maximum/minimum price, and the length of the negotiation:

- Mood - Affects the length of the trading.

- Wealth - Determines the trader’s ideal price range.

- Interest - Influences the magnitude of price adjustments during negotiation.

Negotiation

Every item you aim to sell has a market price. Before each trading session, an ideal price and an auto-acceptance threshold are set.

The first trade always guarantees success (they’ll never reject your initial offer, so feel free to experiment!). The underlying logic is robust—delving into details might spoil the fun—but after the player makes a counteroffer, the trader’s counteraction is generated along with what we call “offer quality.”

Offer quality is a spectrum of thresholds that adjust the trader’s stats based on their perception of the player’s actions. For instance:

- The market price of an item is 200 credits.

- The player asks for 400 credits.

- The trader deems the offer poor but, given their interest in the item, counters with 300 credits — a significant jump from 200.

- Because the offer was categorized as “bad,” their stats decrease.

- The player then requests 350 credits.

- The trader, now with diminished stats but still quite interested, offers 310 credits.

- And so on…

Incorporating these offer qualities adds a layer of complexity to trading, maintaining both predictability and tweakability (is that even a word?).

More?

Cardbob has actually much more to offer, and to cover all of that, this one blog would be very, VERY long. So I’m going to split this into multiple parts, each one dealing with a different part of the game (from features, to marketing). This page will be updated with links to those parts as they are published.